When I find historical texts published in the middle of the 17th century I feel I’ve won the lottery. Even though most authors of this time-frame write flowery 'epistles', or a long convoluted 'introduction to the reader', interspersed with Latin or other languages (Greek comes to mind) which I cannot read, once I finally get into the heart of the book, it yields great information.

|

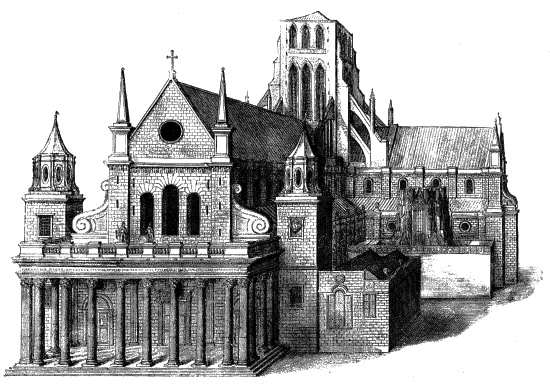

| St Paul's in the early years |

Lately, I've run into historical texts about the physical

condition of London’s old St Paul's Cathedral. The information is very

interesting in that the old fellow lived a full life. The great church could

have regaled us with stories from the blessed to the morbid. When the cathedral

finally met his demise, he went down in a blazing coat of fury.

Surprisingly, for a good while it was a crumbling piece

of rubbish, both structurally and spiritually. After reading, I really wonder if

Godly services ever took place in the building.

In 1658 William Dugdale published The History of St Paul’s Cathedral, and dedicated it to The

Right Honourable Christopher Lord Hatton, Comptroller for the Household to the

late King Charles (the first), and one of his majesties most honourable Privy Council.

Mind you, this was during the Interregnum when Cromwell was in power. A year prior, no one would have attempted to do dedicate a book to a Royalist,

but by this time, the underpinning of the Commonwealth was already weakening,

as was the Puritan leader's health. Cromwell died in September of this same year,

a catalyst to restore the Royal Stuarts. Times were definitely a' changing.

A short history: The cathedral build began in 1087 and

took 200 years to finish. In 1255 part of the church was lengthened, which

swallowed up St Faith, a nearby parish church. The parishioners were given

space in Paul's crypt (called St Faith under St Paul’s) where booksellers and

their families worshiped. Toward the end of Paul’s life, as a safety

precaution, St Faith was used as storage space for their books/papers/printing

presses.

|

| St Paul's after the 1561 fire |

In 1561 lightning struck St Paul’s spire where it caught

fire and fell through the roof of the nave. The fire melted the cathedral

bells, and lead covering the spire melted off the roof like molten lava. Queen

Elizabeth sent letters to the Lord Mayor, pleading for a quick repair to the

roof. She donated from her own purse 1000 marks, and lumber from her

woodlands. Almost 7,000l were

allocated. Within a month of the fire, they began to rebuild the roof, hastily

covering the wood with lead. The spire was never replaced, the reconstruction of

the roof poorly done, yet this still took 5 years to complete.

As a result, St Paul's continued in ill-health for the

next 60 years. Inigo Jones was given the task to refurbish the great, moldering

cathedral while under King James I, but squabbles broke out regarding the

architectural style, and money became scarce. Nothing happened for another 8

years. Then King James died.

Under Charles I, reconstruction was again attempted. This

time, all donated monies were to be recorded, with instructions on what to do

if a donor died without a will. The committee to rebuild the Cathedral would still

get their money. Contributions flowed into London. The renovations became one

of national pride. Over 10,000l had been gathered. By the end of 1632,

repairs began. By the end of 1639 almost 90,000l had been collected.

Houses around Paul's were demolished to make room for the reconstruction. Money

was handed out to those who lost their homes; donations continued to flow in,

sums were divvied for the repairs, then in 1641, everything came to an abrupt

halt.

Civil wars engulfed the country; King Charles was at war

with his own people. Parliament men, and their followers, defaced churches,

including St. Paul's. The cavalry stabled their horses in the church, pulled

down Paul's cross, and other crosses around the city and country. King Charles

I was executed, and Oliver Cromwell moved into Whitehall Palace.

During the Puritan era, in Dean Milman's words, '...St.

Paul's became a useless pile... The portico was let for mean shops... The body

of the Church became a cavalry barrack.' The roof began to leak.

|

| Paul's Walk as Wenceslaus Hollar would have it. |

Then there was Paul's Walk.

As far back as the 14th century, abuses abounded in St

Paul's, which seemed no one had enough power to stop. The nave extended the length of the Cathedral. It was long and vaulted, open to

the public during all hours of the day and night. It became a sheltered

shortcut across the churchyard, a meeting place for all and sundry, a

marketplace of sorts. Young men threw stones at birds that nested there; some

hurled arrows from crossbows, breaking statues and windows. Servants out of work

gathered at a pillar to make themselves known they were for hire. Fights and

brawls further sent the Cathedral into decline. The authorities tried to stop

these transgressions through excommunicates and whatnots. By the 17th century,

the governments were in disarray, and the abuse continued. St Paul’s nave

remained a place of London's underbelly, especially at night.

Charles II returned to England in a blaze of joy and

celebration May 1660. In 1663, a scaffold was built around St Paul's, money

collected, and more houses designated to be pulled down in order to make room

for the rebuild. Architectural design was again argued. A committee of

commissioners had a meeting on August 25, 1666. The repairs would be extensive

from the old foundation to the pillars up to the roof. The steeple still had

not been replaced from the 1561 fire, and a new one fell into the discussions.

But before anything could be done, a fierce wind blew,

and in the early hours of September 2nd, 1666 a fire started in a bakery on

Pudding Lane. Flames blew with the winds and spread at a rapid rate, burning almost

everything within the old London walls. St Paul's, too.

The scaffolding and other demolition around Paul's

hampered any fight to save the old building. Its disrepair only fueled the

fire. St Faith's under Paul's was loaded with combustive goods that exploded,

sending Paul’s choir into St Faith. The lead surface of the roof began to

melt in folds and rained down the sides of the church, into the streets. Within

hours the great Cathedral was a cavernous loss.

|

| St Paul's after the fire of 1666 |

I guess all good things must pass. St Paul’s lasted for

centuries, mostly in some sort of disrepair. Sad, really.

Many thanks to:

Dugdale, William. The History of St Pauls Cathedral in

London from its Foundation until these Times: Extracted out of Originall

Charters. Records. Leiger Books, and other Manuscripts. Beautified with sundry

Prospects of the Church, Figures of Tombes, and Monument. London 1658.

Longman, William (F.S.A). A

History of The Three Cathedrals, dedicated to St. Paul in London. London

1873

Simpson, W. Sparrow (D.D.,

F.S.A). Chapters in the History of Old S. Paul’s. London 1910.

You can find my novels here: http://www.amazon.com/Katherine-Pym/e/B004GILIAS

Very interesting, sad really that it didn't reach its full potential.

ReplyDeleteYes it is sad. A physical structure that saw terrible abuse. :-( Thanks for you comment. Appreciate it.

DeleteVery interesting piece of research!

ReplyDeleteThanks Ann. Those books from earlier centuries certainly are eye openers.

DeleteVery impressive, Katherine. I just love those old, out of print books for my own research. The internet has done much to preserve some real gems.

ReplyDeleteSo true. I found some excellent old texts published in the 17th century for my The Barbers. Without them, my story would have fallen flat. Thanks for reading my blog.

DeleteGreat post, Katherine! The London-Before-The-Fire was quite a different place afterward, and this is a wonderful bit of research--full of stimulating ideas--shared with the rest of us. :)

ReplyDeleteThanks so much Juliet. My novels will go until the fire of 1666. Not sure what I'll do then. I'm into 1664 with only two more novels to go after this one publishes. I do know of a lady in the 17th c. who was far advanced for her time. I might write something about her. I just wish I was better with math and science. :-/

DeleteThank you for this very interesting piece. I thoroughly enjoyed the read.

ReplyDeleteBarbara, so glad you enjoyed it.

Delete